HUD has released 2015 building permit tallies. AustinвҖҷs tallies for 2015:

- Single Family Units: 2,846

- Duplex units: 326

- Units in 3-4 unit buildings: 30

- Units in 5+ unit buildings: 6,890

This bipolar split is typical of American cities. Some cities buildВ more single-family than multi-family. Some build more multi-family than single-family.В But the fourplex is dead. We build very little small-scale multi-family these days,В which is why the вҖңmissing middleвҖқ is a focus of zoning code rewritesВ and a meme among the New Urbanist crowd.

AlthoughВ вҖңmissing middleвҖқ housing couldВ easily be added toВ established single-family neighborhoods while preserving вҖңneighborhood character,вҖқ it is mostly illegal in Austin and most otherВ AmericanВ cities, at least within the single-family districts, and it is often staunchly resisted by homeowners in older neighborhoods, where the form of housing makes most sense. Some homeowners, in fact, seem to dislikeВ вҖңmissing middleвҖқ housing more than any other kind of housing. It is worth thinking about why.

ItВ is useful to first think aboutВ building technologies.В В After manufactured housing, the simplest, cheapest housing technology is the low-rise, wood-frame construction used in В detachedВ single-family homes.В Small apartment buildings can be built using essentially the same techniques. Most large suburban apartment projects, in fact, are developed as a cluster of two-three story buildings containing 8-12 units each. These buildings would actually form nice low-rise, urban neighborhoods if they were arranged around a public street grid, but instead they are arranged around parking lots, private drives and landscaped common areas in garden-style developments.

The next step up from low-rise, wood-frame technology is the mid-rise apartment building of four to seven stories. This type of development requires elevators (and thus a concrete elevator core) and usually consists of вҖңstick and brickвҖқ construction over a concrete podium. ItВ is at least twice as expensive per square foot as similar quality single-family housing вҖ” more if it includes structured parking.

The next step up from the mid-rise technology, of course, is the high-rise which requires concrete or steel framing to the top, structured or subterranean parking, and compliance with stringent fire and building codes. High-rise construction is at least twice as expensive as mid-rise construction.

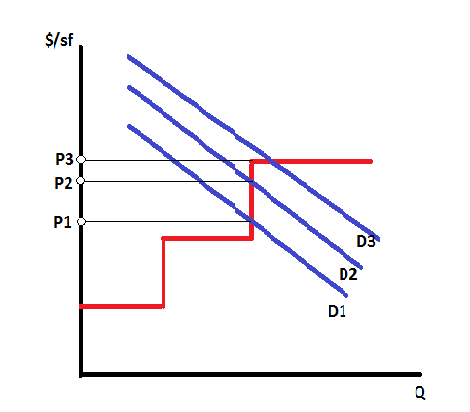

Housing supply is вҖңlumpyвҖқ because of these abrupt changes in construction costs as the market moves from one type of housing to the next. Because it is much more expensive, on a per square foot basis, to build mid-rise housing than single-family housing, and much more expensive to build high-rise housing than mid-rise housing, the supply curve for housing within a neighborhood looks something like the stair-stepped red line:

To grossly oversimplify things, once a neighborhood is built out with one type of housing, it becomes impossible to build new housing without switching to an abruptly more expensive technology. TheВ supply curve remains vertical until the break-even price point at which the new technology becomes feasible. Once the break point is reached, it is possible to add many new units at roughly the same per-unit cost.

The graph above illustrates this: between prices P1 and P2, housing supply is perfectly inelastic. An increase in demand from D1 to D2 translates into a sharp increase in prices without any increase in supply. The new priceВ P2 is still too low to spur new supply. But at P3, there is a sharp kink in the supply curve where the next technology becomes feasible. An increase in demand from D2 to D3 triggers a sudden burst of new construction. And the neighborhood (or at least the choice lots zoned for it) rapidly fills up with the next housing type.

(Note that not even vulgar Econ 101 predicts that housing pricesВ will drop after a switch to a more expensive technology. The switch merely prevents prices from continuing to riseВ because new supply can continue to be added at the sameВ cost.)

As noted, this model is a gross oversimplification. Supply curves are never perfectly horizontal because land costs increase as lots fill up with new development, even if per square foot construction costs remain flat. There is also a substantial lag between a spike in demand and the actual delivery of new supply, since the new supply takes a long time, perhaps years,В to plan, permit and build. The surge in new supply thus tends to coincide with a peak in housing prices. Neighborhood residents (particularly those being priced out) infer that rising densityВ isВ theВ causeВ of the high prices.В They forget that prices were spiking when the market was static.

Although supply curves are never perfectly horizontal, they are, unfortunately, often almost perfectly vertical due to zoning. If zoning limits housing within a neighborhood to detached single-family on aВ minimum lot size, then housing supplyВ within that neighborhood becomes perfectly inelasticВ once the lots areВ built out. Any increase in supply must come from the conversion of low-intensity commercial tracts or older multi-family tracts to mid-rise apartment buildings, which will happen only after a sharp spike in single-family home prices. These commercial and multi-family tracts tend to beВ on the neighborhoodвҖҷs periphery, which explains the pattern of low-intensity single-family housing ringed by abruptly larger multi-family development that prevails in Austin and many other sunbelt cities. This is just the stair-stepped supply curveВ stamped into the built environment.

Neighborhood supply curves areВ not vertical due to technological constraints. Switching from detached single family to duplexes does not require a change in technology: the same low-rise, wood-frame construction will do just fine.В Likewise,В going from the duplex to the four-plex does not require a change in technology, even if the four-plex is slightly more expensive per square foot to build. It isВ in factВ possible to useВ low-rise, wood-frame construction to build accessory dwelling units,В duplexes,В three-plexes and four-plexes, row homes, courtyard homes, manor homes, dingbats and other low-scale housing types. Most of these cost more to build per square foot than detached single-family homes, but they are cheaper than mid-rise construction with concrete elevator cores. If we legalized the missing middle, the supply curve would not have the oddВ stair-step shape, but wouldВ be more smoothly curved. Neighborhoods wouldВ display a continuum of housing types rather than sharp transitions from single-family to mid-rise construction. Five-story apartment buildings would seem like a natural progressionВ of existing density (as they do in AustinвҖҷs West Campus) rather than an abrupt shift. More housing couldВ be built at lower cost, and fewer people would suffer suddenВ price shocks.

Liberalizing the code to allow more low-rise housing seems like it should be an easy sell politically. After all, opponents ofВ zoning liberalizationВ usuallyВ claim thatВ they are trying to preserve вҖңneighborhood character,вҖқ and it is possible to sprinkleВ single-family neighborhood withВ low-rise, wood-frame buildings that lookВ like single-family homes even if they harborВ multiple units. What could be more respectful of neighborhood character?

But some of the most ferocious neighborhood resistance comes to exactly these sorts of small-bore proposals. Austin just went through a knock-down fight over liberalization of the accessory dwelling unit rules. В IвҖҷve been following Austin land-use politics for 15 years, andВ was still surprised by the ferocity of the opposition to small backyard cottages.

This is where the вҖңclub goodsвҖқ view is useful. Homeowners in pricey, established neighborhoods have an incentive to oppose zoning liberalizations that threaten to enlarge the potential size of neighborhood membership and increase othersвҖҷ access to neighborhood amenities. В TheyвҖҷre motivatedВ less by concerns with traffic, noise, or вҖңneighborhood characterвҖқ than with minimizing the neighborhoodвҖҷs carrying capacity. Patiently lecturing themВ about the virtues ofВ вҖңmissing middleвҖқ housing will get youВ nowhere. Garage apartments, duplexes, four-plexes and other missing-middle types are not innocuous additions to the neighborhood housing stock, from their perspective; they areВ a realisticВ threatВ to growВ neighborhood membership quickly and inexpensively. ThatвҖҷs a bad thing, not a good thing, if youвҖҷre seeking to to minimize club membership.

In fact,В someВ homeowners in older, pricier neighborhoods, if forced to allow more housing, prefer to upzoneВ peripheral В tracts forВ mid-rise developments rather than to loosen the restrictions against the missing middle in the neighborhood core.В The mid-riseвҖҷs high construction cost provides some protection against new housing supply. (AndВ many lots on the periphery will have poor access to the neighborhood amenities anyway вҖ” again, a feature, not a bug.)В In Econ 101 terms, homeowners in theseВ neighborhoods wantВ aВ stair-stepped supply curve. Not surprisingly, thatвҖҷs what our zoning codes tend to allow.

[Originally published on the blog Club Nimby]

Pingback: Seattle development and the вҖҳmissing middleвҖҷ problem – Tim Houle()